|

With your favorite fly tied to your line, you approach the swirling and gurgling stream. The water flows smoothly, gracefully navigating around scattered rocks that contribute to the creation of delightful deep pools. You observe the water's dance, and identify potential casting spots. Mindful of your breath, you survey the surroundings and ensure ample clearance for your cast – a breath in as you pull the rod back, and a breath out as you release the line. In this rhythmic motion, we witness the line and fly moving as if in slow motion. The delicate fly touches the stream, embraces the current, and gently submerges, floating through a bubbled surface. Here, we patiently watch, attuned to any subtle motions. Each of these moments possesses a unique significance, inviting us to pay attention. In each step and with every action lies the essence of "Stillness." This is the place that we want to be when we are fishing. There's profound peace in simply observing the fly in the water. The act itself is what it is. In the right place, at the right time, with focused attention, I may witness the fish rise, or sense its subtle pull. Sometimes it happens, sometimes it doesn't. Yet, this outcome is inconsequential. I return to my breathing, find my center, and embark on the process anew. Have you ever found yourself in this mindful state? It surpasses the notion of simply being "in the zone"; it's a wondrous and life-affirming experience. While the desire for flawless tenkara technique is enticing, achieving stillness requires practice and mental preparation. Above all, it involves surrendering to and observing only what is directly in front of us – a skill greatly enhanced through meditation. I can reflect on my own past experiences. There have been times when in my excitement to be on the water, I have rushed in like brute, casting without careful observation of my options. Each instance of neglecting to look behind me for back-cast room leading to moments of frustration, coaxing my fly from the trees or, worse, snapping my line. These actions stem from what my Buddhist teachers of the past call "desire mind" – a tendency to hastily push forward. Stillness is always there if we decide to look for it and be with it. It's essential to clarify that "stillness" doesn't equate to being stationary or devoid of movement. When observing a peacefully flowing river, finer details may elude notice initially. Our minds propel us too swiftly, causing us to miss these subtleties, as if they don't matter. We inadvertently separate ourselves from the stillness that permeates our surroundings. Slowing down our minds so that we can notice there are no ordinary moments. Stillness must be actively sought to be experienced. It exists everywhere, even in a bustling city, in traffic, or within a conversing crowd, and all we have to do to find it is to slow down, and see the chaos as a single thing we are a part of. Stillness begins within our minds, necessitating the quieting of that secondary voice within our heads. I promise you that it is right there waiting to be found. We are very capable of letting everything drop away. Athletes in large arenas talk of this all the time. From professional baseball pitchers on the mound to Olympic skiers. For us as tenkara anglers the crowds are much smaller. We have less to block out and perhaps more to take in. As we walk along a bank we can feel our feet, watch the water, and enjoy the fresh air. And all we have to do is try to keep your mind from interrupting. Simply said, but slightly challenging perhaps? During my winter retreat from the backyard hermitage, I've become acutely aware of the part of my thinking that tends to divert my focus from the present moment. This inner voice, tempting and familiar, often emerges when I close my eyes during meditation, weaving a tapestry of "what ifs" and memories. In many ways, this aspect of our minds resembles a child, vying for attention. What can we do? We allow this mind to run free for a moment or two, and then gently guide it back to a focal point, perhaps assigning it the task of following our breath in and out, or focusing on what silence sounds like. Finding stillness, whether by a stream, in a garden, at a computer, or in the company of others, is a collective endeavor. It involves being fully awake and connected to the present moment, forsaking regrets of the past or the relentless push towards the future. Those things exist in past and future and are not part of the present. In a society that incessantly propels us forward, laden with the pressures of jobs, responsibilities, and the pursuit of elusive dreams – all antithetical to stillness – we must consciously resist. Life compels us to be somewhere other than where we are, often at the expense of savoring the simple joys of a good meal or quality time with loved ones. Stillness has become the primary focus now of my practice. Being present to observe everything in my immediate place of attention, the world slows down and all of those moving parts become part of the greater picture. We realize soon enough that everything is moving, and that “stillness” happens inside our minds when that second voice is quiet. We become part of all the things in front of us and we understand our place. Take a moment each day to find silence, and to just observe the world in front of you. Feel your feet under you, feel the air, see the colors, and watch life in motion. I hope that you pursue this practice of stillness and learn to embrace it with every part of yourself.

0 Comments

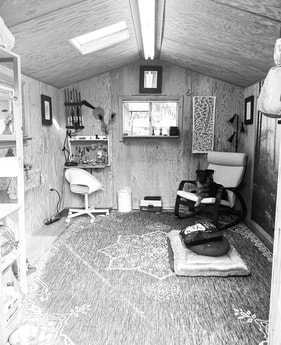

Taking a Long Winter Retreat  Kanji for "Winter" and "Mindfulness" Kanji for "Winter" and "Mindfulness" "Zen is not putting anything into your pocket. It is actually just checking what is already in your pocket." Zen Master Suzuki Roshi As the days grow shorter and a noticeable chill embraces the air, it becomes evident that my fishing season has concluded until spring. This annual decision marks the transition from the riverside to the warmth of indoor activities. Cold water, icy conditions, and slippery riverbanks don't hold much appeal for me during the winter. I'd much rather retreat to a cozy cottage with a good book or spend time at my fly-tying vise, savoring a glass of amber-hued liquid. Cultures worldwide have long recognized the wisdom of winter retreats, drawing from ancestral traditions that offer physical, mental, and spiritual benefits. My personal connection to winter retreats stems from my days as a student of the Kwan Um School of Zen, where they practiced an intensive meditation retreat called "Winter Kyol Che." Although I no longer attend the school, I continue to embrace the concept of retreat, including a 20-day solo retreat in the mountains just over a year ago. Thus, I've decided to create a winter retreat experience at home, combining my past experiences. My plan for the upcoming months: For the next three months, I'll be taking a more adapted and measured approach to my winter retreat. Rather than getting lost in idealized images of a retreat, I've grounded myself in the idea that retreats are about being present, not dwelling on the past or projecting into the future. I won't be shaving my head or climbing to a mountain top to meet a Zen Master; instead, I'll be conducting this retreat from my home. Traditionally, the Kyol Che retreat involves distancing oneself from home, family, work, and the outside world. However, I will only travel as far as my backyard to reach my 10" x 12" shed, which I affectionately call "my tenkara adventure hut" (although it needs a better name). This space houses my camping gear, serves as my fly-tying haven, and is home to my meditation cushion. It's the most fitting place for my retreat. Embracing "Monk Mode": During the retreat, I'll transition in and out of what I call "monk mode." My focus will be on my practices, spending considerable time in my hermitage (formerly known as the shed). Most importantly, I'll remain unplugged from news and social media, fostering a deep connection with myself and my mind. This approach allows me to maintain a balance between retreat and the outside world, enabling me to work periodically and spend quality time with my family.

A Peek into My Hermitage:

I've intentionally kept my hermitage simple, with minimal distractions and access to reading materials. Fly tying serves as my meditative practice during the winter, and I anticipate a surplus in the spring. With electricity in the space, I've installed a space heater and a hot pot for tea. I've stocked a few essentials for lunch and snacks, but I'll mainly prepare my meals in my house's kitchen and bring them to the hermitage. My house will continue to be my primary space for sleeping, cooking, and bathing, while the hermitage offers seclusion for my retreat. Yes, there is a chair as well for Fezzik to hang out on when he wants. A Flexible Schedule: I've drafted an initial schedule to guide my regular meditation sessions, walking meditation, and mindfulness practices for work and meals. However, I expect to modify it weekly, if not daily, as flexibility is vital for success. This schedule serves as a guideline to follow each day. The retreat will take place during the holiday season so I will have a few days where I will likely get at least one session of sitting meditation in on those days. I have decided that the schedule should never feel like a burden. I want to be gentle with myself on some days too.  Embracing the Winter Silence: In the Zen tradition, "Noble Silence" is a key element of most retreats, fostering deep meditation and concentration. As a solo retreatant, I'll strive to maintain silence throughout "monk mode", quieting both my voice and my thoughts. On those occasions when I am out in public I will avoid impulsively expressing thoughts and opinions without consideration. Future Updates: I've already prepared most of my December blog post, and I may include updates on my practice when I post it. As for January, it's too distant to plan for at the moment, and I might skip a January posting. If you have questions, feel free to leave them in the comments below, and I'll try to address them when I post the December blog. Regarding My Etsy Shop: I'm aiming to reopen my Etsy shop for a few weeks in mid or late November. During my work practice time, I plan to craft items suitable for the holiday gift-giving season. We'll see how that unfolds. I hope that these insights into my retreat inspire you to allocate some time for yourself, allowing you to step away from your autopilot routine. Retreats like these have guided me toward a better life and a greater appreciation for the small joys that many of us tend to overlook. I wish you peace, health and happiness through the winter months.

-Dennis Last month, I embarked on a memorable trip to Austria, filled with fishing adventures and cherished moments with friends. The culinary delights transported me back to my days in Germany during the late '80s and early '90s. The trip was nearly perfect, but a major setback awaited me: my luggage was lost on the way to Austria, separating me from my clothes, waders, boots, my beloved Lucky fishing hat, landing net, one of my rods, and my fly tying kit. While some airlines are usually reliable in reuniting travelers with their lost luggage, British Airways let me down completely. As you can imagine, this created immense stress and frustration. Today, we are going to explore the concept of "acceptance" as a practice in life. Accepting may initially sound like giving up, but it's quite the opposite. In a society that often encourages us to "fight on" and "never give up," we often overlook the peace and power that accepting our circumstances can bring. Accepting doesn't mean quitting; it means acknowledging and maybe surrendering a little to what actually is in front of us. It allows us to transition from struggling to stay afloat to calmly navigating our situation and eventually finding solid ground and even finding strength. When we accept a situation, we acknowledge our position relative to that moment and stop resisting it. This shift enables us to flow with the current, maintaining a calm disposition that allows us to make informed decisions.

I must emphasize that I had to intentionally practiced acceptance throughout each day as I inquired with the airline about my missing luggage. It is a very intentional action. Even as frustration mounted each evening, I remained polite, calm, and patient when speaking with customer service representatives. Unfortunately each time I was also, in essence, lied to with promises it would arrive "by tomorrow night" When the fourth night came and I still had no luggage, I made a conscious decision to also accept my growing frustration and anger. I allowed myself to feel these emotions, but because I was in control of my actions, I expressed my anger in a (mostly) controlled manner when speaking to the customer service representative on the phone. It's essential to remember that emotions are part of being human, and it's advisable to opt for a kind and gentle approach first. When that fails, it's acceptable to express anger, but we must also remain in control of that anger. We are the ones in control and not our anger.

I explained that if the airline couldn't do their job, I had every right to express my frustration. As the matter had been presented three times "nicely" without results I was forced to express my feelings much more strongly to be sure I was being heard and not ignored. "Your company has my property and has the job of getting it to me, and your company is failing to do that"

After delivering my frank and semi-controlled feedback laced with some very potent vernaculars, I could tell that he was taken aback. At one point he even asked me to not yell at him. Which I reminded him that this was not about him but the company and that my anger was definitely not for him to take personally but to take action about and as a representative of the company to listen to and act upon. (Fair point I think you can agree.) At this point he attempted to offer a scripted apology. I stopped him there and I refused to accept it because it was the same canned statement I had heard over and over already. Corporations really need to work on this element of communication. So I then shifted into my role as a communications educator, instructing him on the components of a meaningful apology: heartfelt emotion followed by a sincere empathy statement with specific emotions named. After some effort, he managed to provide a more heartfelt apology, and I could sense, like many of the students I train, that he was beginning to understand the importance of genuine empathy in an apology. I did finally accept his apology. I also maintained control of the conversation. I encouraged him to approach every customer as if he knew them personally, to consider the nature of his job, which was not merely to placate customers but to help them solve their problems. I gave him permission to show actual empathy and compassion, as that's what customers expected and need. In the end, I asked him to imagine how I felt and why. While the airline tried once more to locate my bags, they could only trace them to Heathrow, London, instead of Munich as promised. It was more than halfway through my trip so I requested that once found they just be shipped back to my home. They would arrive two days after I returned. Choosing acceptance is not a sign of weakness. We can accept our situation while acknowledging our emotions. We don't have to suppress or immediately express our feelings; instead, we can channel them in a controlled, purposeful manner, devoid of frenzy or violence. Now, turning to the subject of tenkara and this application of acceptance, it's worth considering how acceptance can be a valuable practice in angling. Fishing situations can sometimes feel like they're slipping out of our control, whether we're missing hook sets, not getting rises at all, getting tangled in trees, or snagged on underwater obstacles. In these moments, we can accept them temporarily, stepping back to "stop fighting" and regain our focus. Once we've centered ourselves, we can address the situation with clarity and purpose. Acceptance isn't exclusive to negative experiences; we can also accept moments of joy. When everything is going well in our fishing endeavors, we can get caught up in the excitement. However, it's equally important to pause, accept, and savor these moments deeply. Take the time to appreciate each fish, the experience, and the emotions that accompany our successful angling days. So, I encourage you to practice acceptance in both the good and challenging moments of life and fishing. It's a powerful tool that can help you navigate through life's uncertainties and make the most of every experience. As a magician I have learned in my craft that our vision is not as we imagine it to be. I have honed my skills as a magician to take advantage of this fact. You see our vision is not a constant linear story we are witnessing. It is very much like a film with lots of pictures being sent to our brains and processed. Between these frames are spaces where a magician can take advantage of and steal a move in a psychological moment. This skill set of mine requires me to know when those breaks in the picture happen. I realized that when I am fishing though I forget this element. I find suddenly that I have forgotten that I don't see everything that is going on and suddenly I have lost another fly to a treetop.

We need to take the practice of both "looking" and "seeing". I know that I get in a headspace some times on the stream and rush from one hole to the next and one cast to the next. But now I am working on learning to "look" and to "see". When we go out onto the water we have a tendency to be too focused on the activity and we glaze over the details of the experience. Our attention is only on the "idea" of the task at hand and we forgo actually stopping long enough to be present to what is happening in the moments. You can take notice when you are starting down this mode of being. We start to rush in and maybe step too soon into the water and potentially scare the fish we are stalking. Or maybe we step into a hole or trip on a tree root. I know that in some of the places I fish that can lead to twisted ankles or even having to crawl up a steep ravine with an injury. So this practice of mindfulness of looking and seeing can actually be life saving. There is actually great added enjoyment when we slow down and look and see. We notice details like rocks, trees, the water, wildlife, and even smells and temperatures. Before we cast we should take a breath and look around us. See our relationship within the picture we are part of and be in our place. When we focus on stopping, looking and seeing we not only become better anglers, seeing fish that we wouldn't have lurking by a rock, but we also find more peace and less anxiousness in the way that we fish. Our casts can become more focused as we watch the line, watch the fly, the drift and the hook set. Then as we watch the fish on the line move as we bring it closer to us we can avoid getting the fish snagged. With a fish to net and/or hand we can take that moment to appreciate the fish for it's beauty and the magic of the moment we have in time and space with this encounter with wildlife. Finally we watch the fish return to the water and we can pause again.

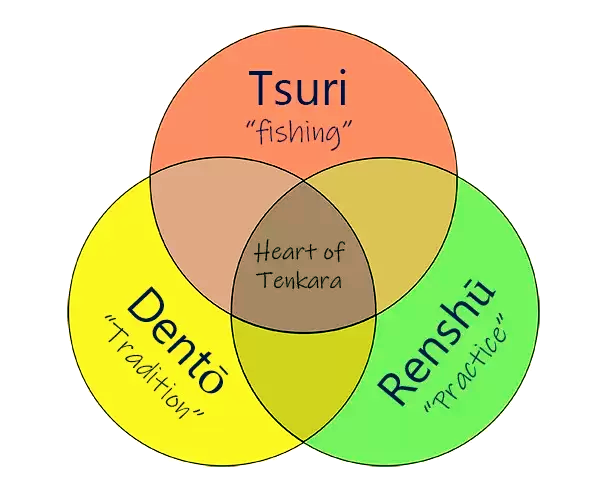

Lately, it pains me to witness the casual disregard shown by some individuals towards tenkara. People continue to write articles, comment on social media and mislead others about tenkara. It is unnerving to me and to those who have respect for tenkara as a practice. I am thrilled to see a surge of interest in tenkara among western anglers. However, in the rush of excitement, many have neglected the vital aspect of familiarizing themselves with tenkara's rich history, culture, and the importance of approaching it with respect as a living practice. Today, I would like to revisit an essay I wrote for Tenkara Angler Magazine about the "Three Paths of Tenkara" in July 2020. It is my hope that readers will pause to internalize these principles and recognize tenkara for the amazing gift it truly is, transcending its label as "just a fishing style" and refraining from misusing the term "fishing tenkara" outside the context of mountain streams. Let us start by establishing a few fundamental agreements. Firstly, we can all acknowledge that tenkara is a fishing style characterized by a rod, line, and fly. Secondly, we must recognize that tenkara and Western fly fishing are distinct approaches with unique histories, techniques, and tackle requirements, much like spin cast fishing differs from Western fly fishing, or deep sea fishing diverges from ice fishing. Lastly, it is crucial to respect that tenkara is a gift bestowed upon us from Japan. It would be culturally disrespectful to tarnish this gift by degrading its form and practice. We have been entrusted with its preservation and it's future. In my own meditations on tenkara I have observed what I call "the Three Paths of Tenkara." they are Tsuri (Fishing), Renshū (Practice), and Dentō (Tradition). Each path interacts and informs each other. Together this creates what I refer to as "the Heart of Tenkara." I will keep it this simple for now. I can go on at length another time with regard to where each intersects. I created the Venn diagram below to help you understand.

As we discern each path in our journey, we gain a profound understanding of the heart of tenkara. At different times in our lives, we may find ourselves walking each path. We may find ourselves walking with the influence of the other two paths subtly shaping our experience. Which path or paths do you identify with? I have little control over what others do with tenkara. I wish there was more reverence perhaps? Please do not consider me a "tenkara elitist". I am not telling anyone how to fish tenkara, I am only saying that tenkara is something specific. Words have meaning and we need to have enough respect for tenkara to not let its definition be trivialized or its form be warped and misused. It is a very western idea that believes tenkara needs to have anything added to it. Tenkara is about reducing fishing to its basic form. Anything you add to it is counter productive to this point. We must ask "just because we can add something...does it mean we should?" Peace, love and fishes Dennis

We must find occasionally in our practice to put the brakes on near full stop. We need to slow down long enough to recognize that life is a fascinating journey. It is filled with ups and downs, lessons, and challenges. In this new year to my life, I continue my practice of tenkara as a tool for living my life the best I can with the years I have left. I have given much thought to the ways that tenkara fortifies my mind, body, and spirit. In many ways, the pursuit of happiness and fulfillment can be compared to the practice of fishing on a tranquil stream. Both involve embracing the present moment, adapting to change, and finding beauty in simplicity. Here are some of parallels between life's journey and the art of tenkara fly fishing I have discovered. There is a wisdom that happens when we look at our lives and tenkara together. It is important to recognize with gratitude that we are on a journey. Embracing Simplicity Means Choosing Honestly Life tends to become complicated as we grow older. We accumulate responsibilities, possessions, and expectations that can weigh us down. While western fly fishing techniques often involve complex gear, intricate fly patterns, and technical approaches, tenkara emphasizes simplicity; stripping away unnecessary complexities. In life, as in tenkara, simplifying our choices and focusing on what truly matters can lead to a more fulfilling experience. It is perhaps easier to simplify one aspect of our lives such as our gear and way of approaching angling. Simplifying our lives in the big picture though is much more challenging. We have to really be honest and decide to take a stand for removing the things that don't add to our lives so we can live it in the best way we can. Develop the Art of Patience As we age, with any luck, we learn the value of patience. In our fast-paced world, waiting is often seen as a burden, or even a torture as we hold back the impulses for gratification. However, tenkara teaches us the art of patience. Standing by a stream, observing the water, and waiting for the perfect moment to cast our fly is a practice that mirrors the patience required to navigate life's challenges. Both endeavors remind us that sometimes, the most rewarding experiences come to those who are willing to wait and trust the process.  Water cuts through it's obstacles by being soft to it. It bends around the rocks, the land the trees. It has no mind of resistance, just of being and moving where it need to go. Along the way it makes its mark on all the things it touches on its journey. Water cuts through it's obstacles by being soft to it. It bends around the rocks, the land the trees. It has no mind of resistance, just of being and moving where it need to go. Along the way it makes its mark on all the things it touches on its journey. Adversity Is Our Friend Life is a constant series of changes. We grow, we evolve, and we face unexpected obstacles. The unexpected arises when we dwell too long and grasp at certain things in life while not allowing things to move. Sometimes they move without us and we grasp to maintain control. Similarly, on a stream, the conditions can shift rapidly, requiring us to adapt our techniques accordingly. In tenkara, the angler must read the water, assess the current, and adjust their approach to match the ever-changing environment. This teaches us the importance of being flexible, open to new possibilities, and embracing change as an opportunity for growth. With gentle practice we can move from one rock to another crossing the stream and from one moment to the next in the same way. When we slow down and are present we can recognize our oportunity to make the best cast by looking at our place and situation from a different perspectives. We can find that better place to cast and drop our fly. We Find Ourselves as Part of Nature and Not Separate from it. In our fast-paced modern lives, we often lose touch with the natural world. Our tenkara experiences provide a bridge back to nature. Standing knee-deep in a stream, feeling the cool water against our legs, and observing the subtle movements of fish and insects brings us closer to the natural rhythms of life. It reminds us to slow down, appreciate the beauty around us, and find harmony within ourselves and the world we inhabit. In short time we lose the idea of separateness from nature and we see ourselves as part of the whole world. In this way we can nurture within ourselves the energy to change our big world lives and outlook. We can begin to make changes in how we are living and can see the ways that we can simplify. As I Age, Cherishing Every Moment Has More Value Getting older often prompts us to reflect on the passage of time and the fragility of life. Tenkara, with its focus on being present in the moment, encourages us to savor every cast, every drift, every gentle tug on the line, and every fish we bring to hand. Life, like a stream, flows inexorably forward, and every moment is a precious opportunity. We must be present in order to take correct actions in those moments. By embracing the present and cherishing each experience, we can find joy in the journey, regardless of our age or stage in life.

Mother, A Cradle to Hold Me By Maya Angelou “It is true I was created in you. It is also true That you were created for me. I owned your voice. It was shaped and tuned to soothe me. Your arms were molded Into a cradle to hold me, to rock me. The scent of your body was the air Perfumed for me to breathe. Mother, During those early, dearest days I did not dream that you had A large life which included me, For I had a life Which was only you. Time passed steadily and drew us apart. I was unwilling. I feared if I let you go You would leave me eternally. You smiled at my fears, saying I could not stay in your lap forever. That one day you would have to stand And where would I be? You smiled again. I did not. Without warning you left me, But you returned immediately. You left again and returned, I admit, quickly, But relief did not rest with me easily. You left again, but again returned. You left again, but again returned. Each time you reentered my world You brought assurance. Slowly I gained confidence. You thought you know me, But I did know you, You thought you were watching me, But I did hold you securely in my sight, Recording every moment, Memorizing your smiles, tracing your frowns. In your absence I rehearsed you, The way you had of singing On a breeze, While a sob lay At the root of your song. The way you posed your head So that the light could caress your face When you put your fingers on my hand And your hand on my arm, I was blessed with a sense of health, Of strength and very good fortune. You were always the heart of happiness to me, Bringing nougats of glee, Sweets of open laughter. I loved you even during the years When you knew nothing And I knew everything, I loved you still. Condescendingly of course, From my high perch Of teenage wisdom. I spoke sharply of you, often Because you were slow to understand. I grew older and Was stunned to find How much knowledge you had gleaned. And so quickly. Mother, I have learned enough now To know I have learned nearly nothing. On this day When mothers are being honored, Let me thank you That my selfishness, ignorance, and mockery Did not bring you to Discard me like a broken doll Which had lost its favor. I thank you that You still find something in me To cherish, to admire and to love. I thank you, Mother. I love you.” I know that each of us has a different relationship with our own mothers. Sometimes a mother isn't always limited to one person who birthed and raised us. Our idea of motherhood is one of being cared for, loved and nurtured. The mother figures in our lives take many forms and can be found in different places. The need and reassurance that motherhood gives us is as Maya describes...that place in our souls where we can be wrapped in the arms of safety. Where we can find light in the darkness and rest our troubles. To all mothers, those who provide motherly love, Happy Mother's day.

With only slight irony, this is the kanji for both "goosefoot" and "wilderness" With only slight irony, this is the kanji for both "goosefoot" and "wilderness" When I find myself feeling the weight of life from living in our so called "civilized world"; I know there is only one place that can really provide me peace and heal me. I go to where my heart, mind and body feel most free. Yes, where trees surround me and reach up to the sky above me. Where the silence is deafening to the noise in my mind. Where I am free of the distractions of humanity.... The wilderness! Watching the news on any source of media these days has become a stress point in my life. On one hand, I want to be informed and on another, the volume of information to process is incredible and is emotionally draining. It saps our joy and love of life. It can make us numb to feeling even the best of emotions. To this point I believe so much in the power and healing we can find in the wilderness. When we stand in the wilderness we make a choice not only to be vulnerable, but to allow ourselves a connection to our impermanence. Nothing can make us more aware of our mortality or the space we occupy on this planet and in this universe than to go where there is wilderness I imagine the questions a zen master might ask their student. "What is this wilderness, and at what point does the wilderness begin or end?" When do we know we are in the wilderness? I suppose for me it is when I find myself surrounded by more of what occurs in nature and there is a noticeable absence of the things that are man-made or human. Going into the wilderness takes a conscious effort for it an exercise in finding ourselves and our relationship to our place in the world. The wilderness is humbling. It can reminds us of our impermanence, and remind us of our relative smallness in the existence of everything. Sometimes when I have been away from the wilderness too long, I have to relearn and rebuild my relationship to it. I have to find my place and know myself enough to become a part of the wild place. I have to listen to it and watch how I handle the moments provided to me. Am I listening? Am I watching? Am I connecting? What is the message the wilderness is telling me and what am I saying to it? Now that spring is upon us, I pine for the pines, the streams, the animals, the mountains, and the elements. As we head up a trail, and into areas where human noises become rare if not heard at all for hours, is that the moment? Is wilderness just a state of mind? A place that exists only in our perception? Is it something that we take with us back to our man made world, held inside our spirit? Can we find that same place when we are surrounded by man-made items, noises and distractions? Perhaps a little if we focus our minds while walking through a park, or sitting under a tree in our yards. We can build birdhouses to attract song birds, and we can landscape a garden to resemble the wilderness. But these attempts are meager at best. The wilderness exists with or without us visiting it. It requires very little of us to exist. And then again it requires us to leave it to its own processes for it to thrive. The wilderness then is perhaps a connection we make with ourselves and our place on this planet. It is our place of ancestral origin. The place that we survived within before clearing spaces and creating a society. When we visit it we are put to judgement for our decision to abandon it. And it still allows us to come back to it but we will never belong again to it for very long. I try to pay attention to the events of my life. What I am doing and what is happening. Inevitable when we slow down to look at our lives we can see a lesson right there for the learning. We need only stop long enough and ask "what is the lesson of this moment in time in my life?"

a few weeks ago, I caught a sinus infection. I think I get one of these about every year in late winter. Each time I get this I go through several stages but it inevitably ends with me losing my voice to the point that I am suddenly able to do a great impression of Tom Waits. (I love Tom but I hate having his voice if it means I have to be in pain using it.) This time around it has lasted almost 3 weeks so far and counting. I am treating it with warm lemon water and honey and that seems to sooth. So as I have been looking at this current state and experience of being without a voice I ask "what is the lesson of this moment...etc...etc? Well... I guess the first thing that comes to mind is "practice silence". It is surprising though how difficult it is to try and practice silence. You can go all day and then suddenly notice that you are speaking under your breath to yourself. Is there a difference between "silence" and "quiet"? We can decide to be silent and not speak, or make noise if we can help it. Then when we stop speaking our thoughts start to fill the space of the audible noises with the noise of thoughts in our head. How do we silence the noise in our heads? Well, meditation practice is a start and I have written about the practice of "NOW MIND" too. With attainment of "now mind" we begin to realize that while there isn't a place of actual silence, there is a place of quietude. Certain noises around us are inconsequential to the moment we are in. When I came home from my long retreat in the mountains last summer, I had become quite accustomed to the silence that is "silence of my mind within the wilderness". So when I stepped out my back door on that first morning back, I realized how much I could hear the sound of traffic, not just near by in the neighborhood, but from miles away. I could hear also aircraft, the hum of my neighbor's lawn mower, and the sound of a sporting event at the nearby park. The sounds felt invasive compared to the type of silence I was used to and it took a while before I could just put them into the background of my day and make them oblivious to my mind. I have to think that they have a subliminal effect on our psyches in the long run. This showed me that there is a special kind of silence we need. It is the special kind of silence that we experience when we are fishing. Quiet happens within ourselves as we quiet our thoughts, the sounds around us in nature we can consider silence. They don't tax our attention or make us feel surrounded by man made chaos but instead by natural chaos. When we find quiet as a state of our minds, we allow the sounds of nature to come and go without much effort. We perhaps enjoy the connection with the natural world in a more intimate way. This kind of practice can also inform us and give us pause to slow down and be aware of the noises we are contributing when we are in the wilderness. We can see that our place in the wilderness has a response if not responsibility to be in that wilderness. In the wilderness we find ourselves in a much more private place. We connect with the sounds, smells, sights, and sensations of the wilderness and we feel ourselves connecting to a natural existence. In this state we become aware of our own noises and we see that we can make a choice to move quietly as we can within it. We practice silence in our actions and as a result we become better anglers too. We can be part of nature and work quietly to come to the banks of the stream without disturbing the fish. So often our noisy minds push us to start casting before we should and don't read the water correctly or we step into the water too carelessly and again too early and disturb the fish that is just hanging out under the banks.. But what about practicing silence in our human affected world? Exercising silence in our day to day lives is a worth while practice. The same practices of just clearing our minds lets us nurture a concept silence may let us observe what is natural and before us. We may find ourselves reserving our actions and our outbursts in situations and when we do act we approach our challenges, conflicts and problems with a grace based in being silent. Even in the hum and chaos of our noisy human places, we can intentionally practice silence. We can create spaces that we can quiet our minds and hone our skills to find quiet in the noisy places. We can accept that certain amount of "mental noise" but allow for quiet to win out. I hope that you find that quiet place in your day to day life and that you also get to experience silence in the wild places when you can.  Kanji for "kawa" = "River" Kanji for "kawa" = "River" “I would love to live like a river flows, carried by the surprise of its own unfolding.” - John O'Donohue I have been wanting to write for months now about my retreat I took in August. There is just so much to talk about though that I thought trying to cover it all in a single article would not give it justice. What I learned and experienced could not really be put into just a few words. It is a big deal to take the time to slow down and just be a human without distractions. I can only say that if you can, you should! The retreat really did allow me to look at myself, my life and my thinking. I had challenging days of sadness as well as deep days of happiness. I lived simply with good food, natural silence, and the loyal friendship of my dog "Fezzik" there to keep me from going totally bonkers. Yes, I did get to do some fishing too. I even found new waters. Coming home from the mountains after 20 days, I continued my retreat from home. It was a great way to transition back to my life. The contrast of living alone in my hermitage in the mountains to being back in my house was quite noticeable. I went from having virtual silence and nature to the overt man made noises invading what we accept as "quiet" in even lightly populated areas. I miss getting up in the middle of the night to let the dog do his watering of small pine trees and being floored by the sky full of stars that made me humble. At home, I still get up at night to let him out but even the blackness of night seems more of a dark grey that isn't quite black and the stars are muffled by ambient light of neighbors who decide that they need a floodlight on in their enclosed backyard. I sometimes believe I could read by that porch light if I needed to. Even when our lives are going well though we may become oblivious to the places that begin to build up and become cluttered. As with any river when too much stuff is flowing down it, it tends to get jammed up. We may not notice the water backing up behind the dam of extra stuff we carry, own and collect. Eventually the pressure builds and we find ourselves in a state of feeling we are a little over our heads in the water. Eventually the dam has to break. But are we going to be part of the reason it does? December was kind of a breaking point for the dam that was building up and keeping my life from moving forward. The cracks in the dam showed up first while I was busy in my woodshop. I had work for both my own shop as well as things for my wife who was participating in a holiday sale. The dam cracked in the form of a shop accident that nearly took out my index finger. I had a mishap with my chop saw and a piece of wood I was cutting. The blade hit the wood and the wood splintered sending a shard of hardwood across my left index finger knuckle. It cut deeply and just barely missed the tendon. Emergency room visit and eight stitches later I had a lot to consider. Was this the end of my woodworking? My work as a professional magician is pretty important to me. Losing a finger as a result of a woodworking accident would be a real life changer. I started to question my life as a wood worker a bit too. It was a preventable mistake that would not have happened if I hadn't been rushing and trying to do so much. Having the down time I was able to focus on what I could have done differently. I decided that I need the break and embraced it. I put my Etsy store on "vacation mode" and refunded the uncompleted orders that had been made. So much for my winter spool sale? Thinking back about the feeling of happiness I had on my retreat, I decided that I really needed was a place at home similar to what I had found on my retreat. A sanctuary from the busy world and a domain dedicated to living slower. Many times the best way to get a new perspective is to just start with a clean slate. ...So, I cleaned the slate alright. I gutted out my woodworking shop. ...And... Transformed the shed into a space for my tenkara, meditation and trip planning. I am avoiding the term "man cave" but looking at it instead as a backyard retreat hut. I can quite easily do daily meditation, have in town retreats, read books, plan trips, tie flies and just let the outside world drop away. One observation through this process was that change is one part letting things happen and one part guiding those changes in the direction you want them to go. What was I going to keep and what was I going to let go of?

Was I going to shut down the shop for good? Was this the end of my wood working? It almost could have been. Once I had moved into and created a new space with the shed, I couldn't think of where I was going to do my woodworking. Our small, one car garage really was the only real option I had left. But it had become a storage pile for everything in our house that didn't have a home. Fortunately, my wife convinced me, in spite of my aversion to the idea, that we could rent a small storage unit. I don't like the idea of paying rent to store stuff I own. But we certainly had stuff that needed to be kept and the space in the garage needed to be worked over. Sometimes we really just need to make space in one area in order to free up space for another. The process of cleaning out items in the garage was a good one. I discovered that we had a lot that we were storing that we didn't need.those things went to charity or were recycled. What was left was actually not as much as I had thought. So, for the short term I am good with the decision to store some of our stuff in the storage unit. The back half of our little garage is now nearly ready to be transformed into a workshop for me. What I noticed through this whole process was that there is a flow to all things. We can fight the flow of life as it comes at us or we can help it move along in a direction that is productive for us. We can drift with it and see where it takes us. I have to credit making the sacred space for myself for also breaking free the other places in my life that had kind of gotten blocked up. My writers block, my creativity in my shop, my need for a place to call sanctuary. I am happy to say that I am in the process of looking not just as the places I have created for myself but also at the life I want to live, the work I want to do and the things I want to accomplish. This new blog format really is the result of that breaking free and going with the flow of life. I look forward to seeing where the life of this river flows. |

TENKARA AS PRACTICEArchives

December 2023

Categories |